Caroline Snow’s path to becoming Senior Partner at Dentons, one of the world’s largest law firms, hasn’t exactly been conventional.

Caroline Snow’s path to becoming a senior partner at Dentons, one of the world’s largest law firms, hasn’t exactly been conventional.

After setting out to study a double degree in law and information technology, Snow quickly found herself pivoting away from tech and doubling her efforts in law. “I was the only female in the tech degree, she says. “And that wasn’t cool back then!”

Today, she specialises in capital raising and funds management, balancing complex mergers and acquisitions and structuring advice, and is a passionate advocate for the not-for-profit and disability services sector.

We chat with her about why taking a human-centered approach to her work is so important, and what she has learned about persuasion and communication along the way.

One thing that stands out in your career is how often you’ve dealt with situations where the stakes weren’t just financial, but deeply human. When have you felt the human side of what you do most acutely?

I’ve felt the human side of my work most acutely through my involvement with not-for-profits in the disability and education services sectors.

As a senior partner, I’ve had the privilege of building an emerging mergers and acquisitions (M&A) practice for not-for-profits in the disability and education services sector. As part of this work, I sit on the board of a not-for-profit that runs allied health and a specialist college for children with language disorders.

What a fantastic initiative. What kind of work are you doing there?

Well, recently our team was advising the board of a regional not-for-profit that operates the only childcare facility, medical centre, retirement village, and aged care home in the region.

This organisation does incredible work for its community, but a couple of years ago it was struggling and relying on government funding just to survive.

Why was that?

The governance burden had simply become too great for such a small-town operator, especially given the increasing regulatory oversight these services require. The organisation just couldn’t continue operating as a not-for-profit service provider.

Our team was part of an advisory group tasked with developing a strategy to convince the not-for-profit — which was essentially the entire town — to sell its community assets to a for-profit provider.

How did that go?

It was a personal and professional challenge, for sure.

The town meeting was incredibly passionate, and I remember having to take the floor to explain the structure, risks, and opportunities of what was being proposed. It was about acknowledging the great job the community had done in holding everything together, while also making it clear that selling was the only viable path forward.

How do you go about explaining something like that to an entire town?

We had government stakeholders, distressed board members, and business advisors parachuted in to support, and by the day of the vote, the pressure was immense. If the vote to sell hadn’t passed, the ambulance service in the next town was on standby to relocate aged care residents to new accommodation.

Thankfully, members approved the sale, and all was well. Now, two years later, everything is running smoothly, and the services remain a real success in the community.

It’s not the biggest transaction I’ve ever worked on, but it was certainly one of the trickiest in terms of the human side of things.

It sounds like the legal side was only half the battle—the bigger challenge was the human one.

Absolutely. And I say this with respect: the human challenge is almost always the harder part.

Do many M&A transactions carry that kind of human impact?

Every M&A transaction has a human impact.

Usually, though, the stakeholders aren’t as vulnerable or as disempowered as the people in that community. They would have borne the greatest consequences if we hadn’t been able to get that particular deal over the line.

I remember standing in front of 300 community members on a cold June night in the regions, trying to explain how the vote and the law worked. The community had never been through anything like it — and why would they? It was extraordinary.

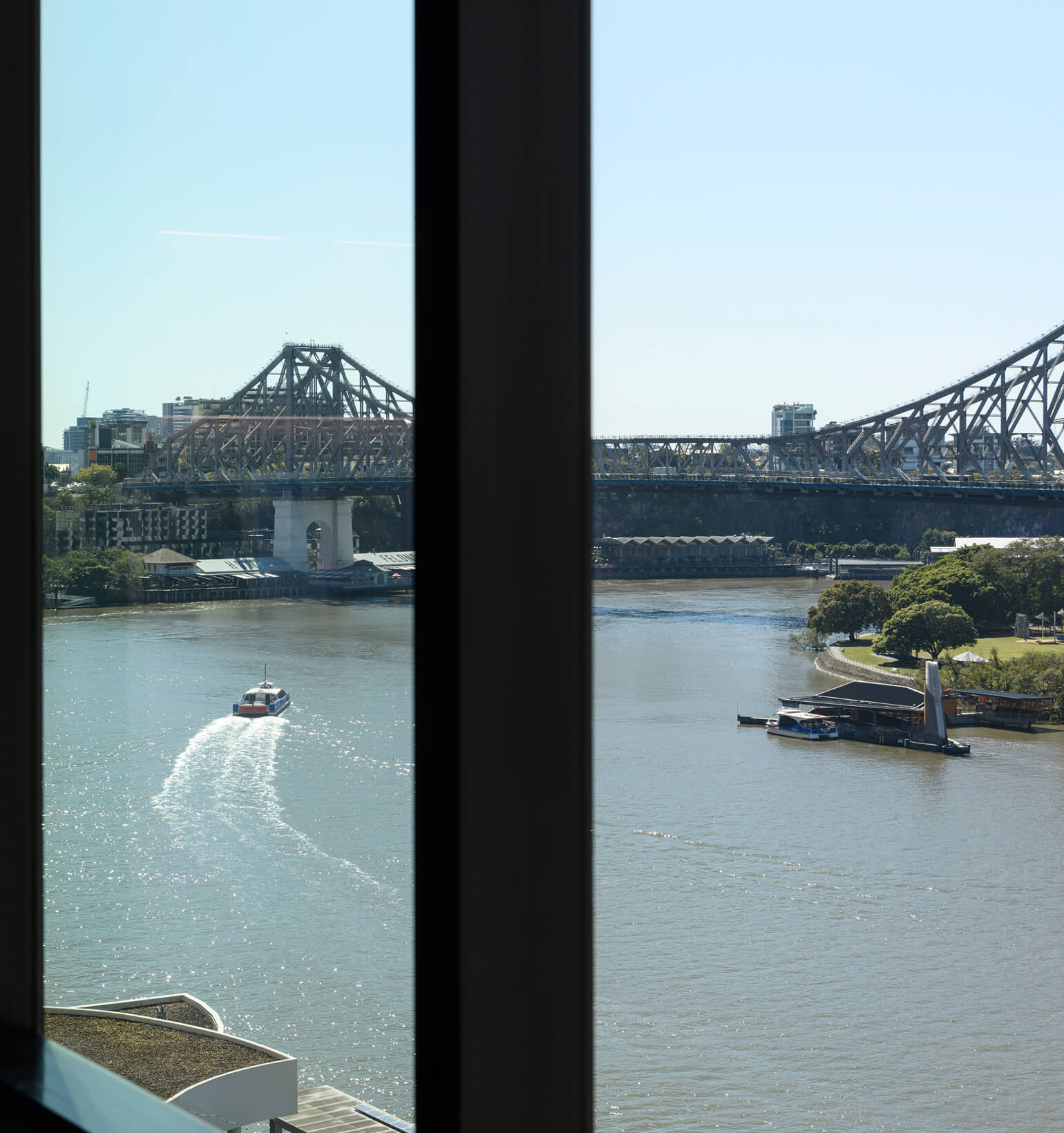

You’ve always presented to boards and serious people in suits, with beautiful views. But then you’re suddenly in a town hall with community members. Did you prepare differently for that?

It wasn’t my first rodeo in front of vulnerable people who had a lot to lose.

The biggest lesson was understanding the real impact financial decisions have on everyday people. That’s something I remind my team of constantly: the way we structure transactions or handle disclosure always flows downstream.

Tell me more about that.

If we go back to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), I was working in-house at a fund manager that became the replacement responsible entity for a very large, very distressed retail fund.

That fund had 14,753 investors — many of them everyday mums and dads, and mostly grandparents — who had lost an extraordinary part of their investment. This was well before Teams and Zoom, so we decided to do roadshows around the country to meet as many investors as we could, to explain what was happening and what the impact would be.

That must have been confronting.

It was. I was a very junior analyst at the time, and it was my first real glimpse of the human side of what volatile investments and misleading disclosure could result in.

The experience left a lasting impression.

What did you take from that time that you’ve since carried into your work?

The biggest lesson was understanding the real impact financial decisions have on everyday people. That’s something I remind my team of constantly: the way we structure transactions or handle disclosure always flows downstream.

I worry less about private equity firms — they have governance frameworks to absorb and manage those impacts. But when there’s a direct personal element, you have to appreciate how those decisions land in people’s lives.

Even regulation, which can feel onerous at times, exists for good reason. Regulators like ASIC and APRA are acting in good faith to create safer markets. We don’t always agree with them, but we recognise the intent.

There’s a science to persuasion. Good advisors understand that, and it’s where I can really add value.

It’s not often we think about the people management side of corporate law…

Clients know that stakeholder management and bringing people along on the journey are some of my strengths. In Brisbane, which is a smaller market, I’m often called in for exactly that reason.

At the end of the day, it comes down to persuasion: how do you help shareholders or members say yes to something difficult?

Ah, the art of persuasion. Is that the language you use or how you show up and connect with the other party?

It’s all of those things. And there’s a lot of psychology in it. I’ve even done postgraduate work on the art of presentation and influence as part of developing my leadership skills.

One of the benefits of my time in investment banking was learning how to build compelling investment opportunities into pitch decks — the order of the slides, the level of detail, how information is presented, even details like the colour of a proxy form or where directors sit during a shareholder meeting. It all matters and can subtly influence the tenor of the proceedings.

There’s a science to persuasion. Good advisors understand that, and it’s where I can really add value.